Before we draw a single box or write a single API endpoint, we need to deeply understand what a news aggregator actually is and what makes it a compelling system design problem.

A news aggregator — like Google News, Apple News, or Flipboard — is a digital service that continuously collects news articles from thousands of publishers around the world, processes and organizes them, and presents them to users in a unified, scrollable feed. The user does not go to CNN, then BBC, then Reuters individually. Instead, they open a single application and see the most relevant, recent news from all of those sources in one place.

Why is this an interesting system design problem? At first glance, this might seem trivially simple: "just pull RSS feeds and display them." But the moment you consider the scale (100 million daily active users), the freshness requirements (breaking news must appear within minutes), the read-heaviness of the workload (users read far more than the system writes), and the need for features like deduplication, categorization, and trending topics, the problem becomes significantly richer. This is fundamentally a read-scaling problem; the entire architecture must be designed to make reads as cheap and fast as possible. That single insight should guide every decision you make throughout the interview.

Let us proceed step by step.

Requirements

Functional Requirements

We begin by asking ourselves: "What must a user be able to do with this system?" We phrase these as "Users should be able to..." statements and prioritize down to the top 3.

Core Requirements

- Users should be able to view an aggregated feed of news articles from thousands of source publishers worldwide. The system must continuously fetch, process, and organize this content.

- Users should be able to scroll through the feed "infinitely." This implies a pagination mechanism on the backend, and as we'll discuss later, the choice of pagination strategy (offset-based vs. cursor-based) has significant implications for consistency and performance.

- Users should be able to click on articles and be redirected to the publisher's original website.

Below the Line (Explicitly Out of Scope):

- Personalized feeds based on user interests/reading history. This is a fascinating problem (and we'll touch on it as a bonus deep dive), but it adds enormous complexity.

- Save/bookmark articles for later reading. A CRUD feature that doesn't affect the core architecture. Trivial to add later.

- Social sharing (share to Twitter, email, etc.). A client-side feature that requires no interesting backend design.

- Push notifications for breaking news. This is a separate system (notification infrastructure) and would muddy the design.

- User comments or reactions on articles. This turns the system into a social platform, which is a different problem.

The reason we are explicit about these exclusions is that the interviewer might ask "what about personalization?" and we want to have already anticipated that. "Great question — I've deliberately scoped that out to focus on the core aggregation problem, but I'd be happy to discuss it as a deep dive if we have time" is a strong response.

Non-Functional Requirements

Non-functional requirements describe the qualities of the system rather than its features. A junior candidate might say "it should be fast." A senior candidate specifies how fast, where in the system, and why that matters. These requirements directly drive architectural choices.

1. Availability over Consistency (AP System)

Consider the alternative: strong consistency would mean that when a new article is published, no user sees it until every replica has been updated. In a globally distributed system, this would add significant latency to every read and make the system fragile during network partitions.

For a news aggregator, the consequences of inconsistency are mild — a user might see a slightly stale feed for a few seconds. The consequences of unavailability are severe — the user sees an error page and leaves. Therefore, we choose availability and partition tolerance (AP) over strong consistency, per the CAP theorem.

In practice, this means:

- We use eventual consistency for feed updates. When a new article is processed, it propagates to caches and replicas over seconds, not instantaneously.

- During a network partition or partial outage, we serve stale cached data rather than returning errors.

- We design every fallback path to degrade gracefully (serve older data) rather than fail hard.

2. Scale: 100M DAU, ~10K Concurrent Requests/Second at Peak

We need to be specific about the scale because it drives decisions about sharding, caching, and infrastructure sizing. 100 million daily active users is Google News / Apple News territory. This is not a small-scale problem. However, stating the number alone is not enough — we need to translate it into request rates to understand the load on our serving layer.

3. Low Latency: Feed Loads in < 200ms (P99)

This is our latency SLA, and it is aggressive. 200 milliseconds at the 99th percentile means that 99 out of 100 users must see their feed load in under 200ms. This immediately tells us:

- We cannot query PostgreSQL on every feed request. A SQL query joining articles with publishers, filtering by category, ordering by timestamp, and limiting to 20 results might take 10-50ms on a warm database — but under load, with connection pooling overhead, this balloons to hundreds of milliseconds.

- We need a caching layer (Redis) that can serve pre-computed feeds in < 5ms.

- We need a CDN to absorb identical requests from anonymous users.

4. Freshness: Articles Appear in Feeds Within 5-30 Minutes of Publication

Users come to a news aggregator specifically because they want current news. If an article was published 2 hours ago and still doesn't appear in the feed, the system has failed its core value proposition. We aim for major publishers' articles to appear within 5 minutes and smaller publishers within 30 minutes. This drives decisions about our polling frequency, processing pipeline latency, and cache invalidation strategy.

5. Read-Heavy: ~1000:1 Read-to-Write Ratio

For every article written into the system, it will be read thousands of times across millions of feed requests. This ratio tells us unambiguously that our architecture must be optimized for reads.

Capacity Estimation

We should not spend 5 minutes calculating exact QPS only to conclude "it's a lot." But there are two numbers worth computing here because they do influence our design:

Ingestion rate (write side):

- ~50,000 publishers x ~50 articles/day each = ~2,500,000 articles/day

- 2,500,000 / 86,400 seconds = ~29 articles/second

This is a modest write rate. A single Kafka topic with a few partitions can easily handle 29 messages/second. A single PostgreSQL instance can handle 29 inserts/second without breaking a sweat. This tells us that the write path is not our bottleneck — we don't need to shard writes, and we don't need complex write-scaling strategies. The challenge is purely on the read side.

Feed request rate (read side):

- 100,000,000 DAU x ~5 feed loads/day = 500,000,000 feed requests/day

- 500M / 86,400 = ~5,800 QPS average

- Peak (assume 3x average) = ~17,400 QPS

17,400 queries per second hitting PostgreSQL directly would be devastating. Even with read replicas, each query involves sorting, filtering, and joining — at this QPS, the database would buckle. This number confirms that we absolutely need a caching layer (Redis) and a CDN to absorb the majority of these reads. If Redis can handle 95% of requests and the CDN absorbs another 40% before they even reach our servers, PostgreSQL only sees a few hundred QPS — entirely manageable.

These two numbers — the modest write rate and the massive read rate — are the quantitative justification for every architectural decision that follows.

Core Entities

Before designing APIs or drawing architecture diagrams, we need to name the things in our system. Core entities are the nouns — the objects that our API will exchange and our database will persist. We start with a deliberately small list and expect it to grow as we work through the design.

Publisher

A Publisher is a news source — CNN, BBC, TechCrunch, a local newspaper. Each publisher has a name, a website URL, and one or more feed endpoints (RSS, Atom, or a proprietary API). We also track metadata about the publisher that influences how we fetch their content: how frequently they publish, what priority tier they belong to, and what their current polling interval is.

Why is Publisher a separate entity and not just a field on Article? Because publisher metadata drives the behavior of our ingestion layer (polling frequency, priority, rate limits). We need to query and update publisher records independently of articles.

Article

An Article is a single news piece published by a publisher. It has a title, a brief summary (which we either extract from the RSS feed's description field or generate by truncating the article body), a source URL (the link to the full article on the publisher's website), a thumbnail image URL, a published timestamp (from the publisher, not when we ingested it), and one or more category tags.

The Article is the central entity of our entire system. Feed requests return lists of articles. Search queries return articles. Trending displays articles. Everything revolves around this entity.

Category

A Category is a topic classification: World, Business, Technology, Sports, Entertainment, Science, Health. Categories could be modeled as a simple enum or string field on Article, but conceptually they are a separate entity because:

- An article can belong to multiple categories.

- Category definitions might change over time.

- Category-based feeds are a core feature, so categories need to be first-class.

For simplicity in the initial design, we'll model category as an enum field on Article (or a junction table if we support multi-category articles).

FeedItem

A FeedItem is a projected view of an Article — it's what the client actually receives when it requests a feed. It includes only the fields needed for display: title, thumbnail URL, publisher name, published timestamp, source URL, and article ID. This is not persisted as a separate table; it's a DTO (Data Transfer Object) that the API constructs from Article and Publisher data.

Why define it as a separate entity? Because the distinction matters for API design. The client doesn't need (and shouldn't receive) the full Article object in a feed response. Sending only FeedItems reduces payload size and keeps the API clean.

API Design

The API is the contract between our system and its clients. We design it before drawing the architecture because the architecture's job is to fulfill this API. Every box and arrow in the diagram should trace back to serving one of these endpoints.

We choose REST as our API protocol. REST maps naturally to our resource model (articles are resources, feeds are collections of resources), is universally understood, and is the default choice unless there's a specific reason to deviate. GraphQL would be useful if we had diverse clients with wildly different data needs, but for a news feed that returns the same shape of data to all clients, REST is simpler and sufficient.

Endpoint 1: Get Feed

1GET /v1/feed?category={category}&cursor={cursor}&limit={limit}Response:

1{

2 "items": [

3 {

4 "article_id": "uuid-123",

5 "title": "Major Climate Summit Reaches Agreement",

6 "summary": "World leaders agreed to a landmark deal...",

7 "thumbnail_url": "https://cdn.newsagg.com/thumbs/uuid-123.jpg",

8 "publisher_name": "Reuters",

9 "published_at": "2026-02-10T14:30:00Z",

10 "source_url": "https://reuters.com/article/climate-summit-2026"

11 },

12 ...

13 ],

14 "next_cursor": "eyJ0cyI6MTcwNzU3MDYwMCwiaWQiOiJ1dWlkLTEwMCJ9"

15}

16Thought process behind each parameter:

- category (optional): If provided, filters the feed to a specific topic (e.g., "technology", "sports"). If omitted, returns the general "Top Stories" feed that mixes all categories. This directly supports the category-based feed requirement.

- cursor (optional, string): An opaque pagination token. On the first request, the client omits this parameter. On subsequent requests (as the user scrolls down), the client passes the next_cursor from the previous response. The cursor encodes the (published_at, article_id) tuple of the last item returned. We'll discuss in the deep dives why cursor-based pagination is far superior to offset-based pagination for this use case.

- limit (optional, integer): How many articles to return per page. Defaults to 20, maximum 50. We enforce a maximum to prevent clients from requesting absurdly large pages that would strain our cache and network.

Why next_cursor is null sometimes: When there are no more results (the user has scrolled to the end of available content), next_cursor is null. The client knows to stop requesting.

Why no user_id in the request: The user's identity is derived from the authentication token in the HTTP Authorization header. Never trust client-supplied user IDs in request bodies — that's a security antipattern. Even for anonymous users, we can assign a session-based identifier if needed for analytics.

Endpoint 2: Get Article Detail

1GET /v1/articles/{articleId}Response:

1{

2 "article": {

3 "id": "uuid-123",

4 "title": "Major Climate Summit Reaches Agreement",

5 "summary": "World leaders agreed to a landmark deal...",

6 "thumbnail_url": "https://cdn.newsagg.com/thumbs/uuid-123.jpg",

7 "publisher": {

8 "id": "pub-456",

9 "name": "Reuters",

10 "logo_url": "https://cdn.newsagg.com/logos/reuters.png"

11 },

12 "category": "world",

13 "published_at": "2026-02-10T14:30:00Z",

14 "source_url": "https://reuters.com/article/climate-summit-2026",

15 "related_articles": [

16 { "article_id": "uuid-789", "title": "EU Reacts to Climate Deal", "publisher_name": "BBC" }

17 ]

18 }

19}

20Why does this endpoint exist if we redirect to the publisher? Because some clients may want to show an interstitial page before redirecting — displaying the full summary, related articles from other publishers covering the same story, and the publisher's name/logo. This is common in Google News's UI. It's a lightweight read from our cache and adds significant UX value.

Endpoint 3: Get Trending Articles

1GET /v1/trending?limit={limit}Response:

1{

2 "articles": [

3 { ...FeedItem... },

4 ...

5 ]

6}

7Thought process: Trending is a distinct concept from the main feed. Trending surfaces articles that are generating the most engagement (clicks, being covered by many publishers) in the last few hours, regardless of category. The backend computation for trending is different from the main feed (it involves counting clicks/coverage, not just sorting by timestamp), so it warrants a separate endpoint.

Endpoint 4: Search Articles

1GET /v1/search?q={query}&category={category}&cursor={cursor}&limit={limit}Response:

1{

2 "items": [ ...FeedItem... ],

3 "next_cursor": "..."

4}

5Thought process: Search is a core expectation for any content platform. The shape of the response is identical to the feed endpoint (it returns FeedItems with pagination), but the backend implementation is entirely different — it queries Elasticsearch rather than Redis sorted sets. The optional category filter allows users to scope their search (e.g., search for "election" only in "Politics").

A Note on API VersioningAll endpoints are prefixed with /v1/. This is a simple but important practice. When we inevitably need to make breaking changes to the API, we can introduce /v2/ endpoints while maintaining backward compatibility for existing clients. In an interview, mentioning this briefly shows awareness of production concerns.

Data Flow

Before jumping into the architecture diagram, it helps to outline the sequence of events that occur from the moment a publisher publishes a new article to the moment a user sees it in their feed. This "data flow" serves as a roadmap for the high-level design.

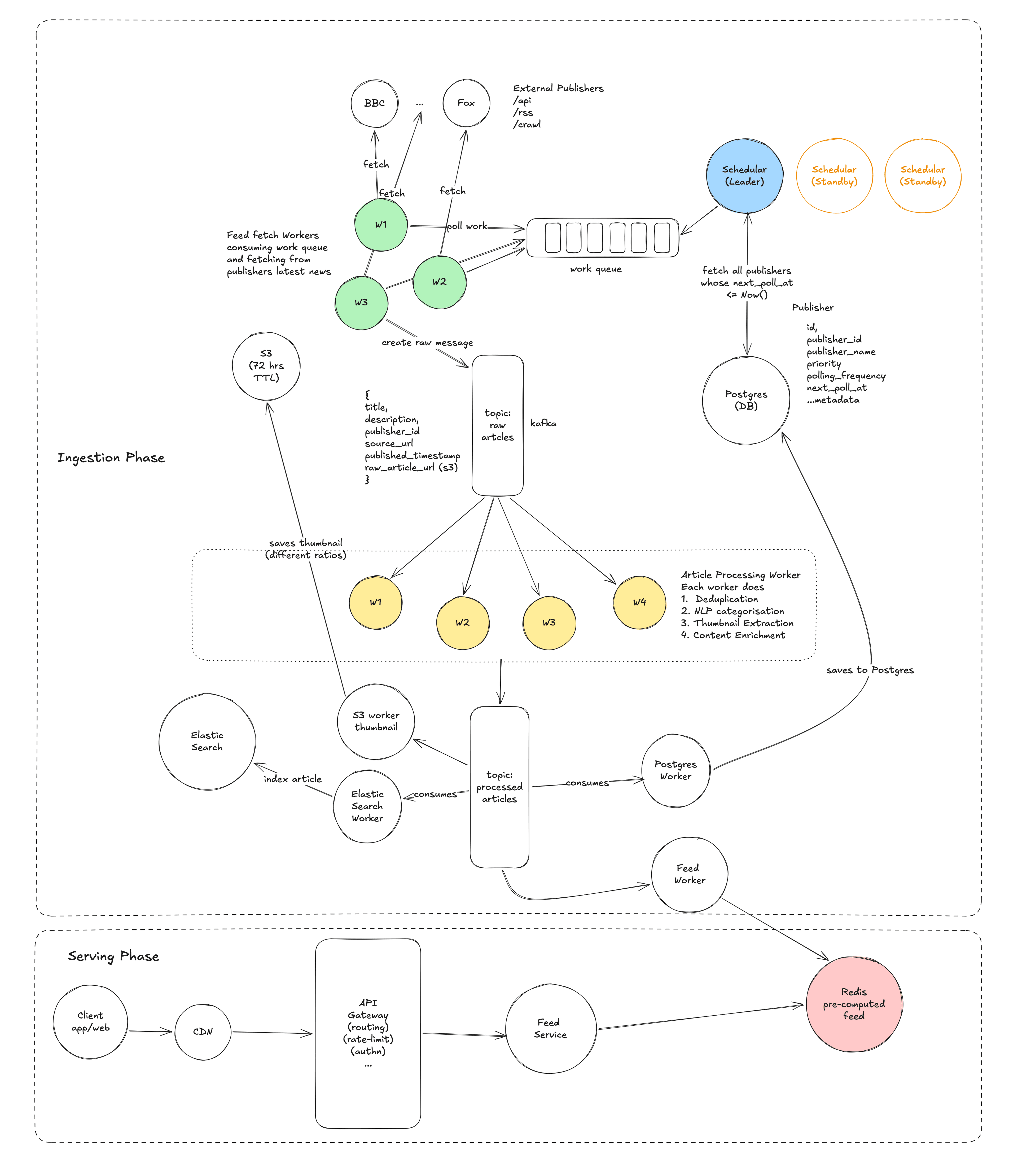

- Scheduling: A centralized Scheduler maintains a registry of all ~50,000 publishers with their polling intervals. It triggers Feed Fetcher Workers to check each publisher's RSS/API feed according to its schedule.

- Fetching: Feed Fetcher Workers download the RSS/Atom/API response from the publisher, parse it, and extract individual article entries (title, URL, description, published timestamp, etc.).

- Buffering: Raw article data is published to a Kafka topic (raw-articles). Kafka acts as a buffer between fetching and processing, decoupling these two stages and absorbing any spikes.

- Processing: A fleet of Article Processing Workers (Kafka consumers) picks up raw articles and performs:

- Deduplication (have we already ingested this article?)

- NLP categorization (what topic does this article belong to?)

- Thumbnail extraction (download and resize the article's hero image)

- Content enrichment (extract a clean summary if the RSS description is inadequate)

- Storage: Processed articles are written to multiple stores, each optimized for a different access pattern:

- PostgreSQL (source of truth for article metadata)

- Elasticsearch (full-text search index)

- S3 (thumbnail images)

- Redis (pre-computed feed sorted sets and article detail cache)

- Serving: When a user requests their feed, the request flows through CDN → API Gateway → Feed Service → Redis (cache hit) or PostgreSQL (cache miss) → response.

This linear sequence — Schedule → Fetch → Buffer → Process → Store → Serve — is the backbone of the entire system. Every component in our architecture maps to one of these stages.

High-Level Design

This is the meat of the interview. In the high-level design, we get a working system on the board. In the deep dives, we make it fast and resilient.

The Architecture Overview

The system is divided into four layers:

| Layer | Components | Responsibility |

|---|---|---|

| Ingestion Layer | Scheduler, Feed Fetcher Workers, ZooKeeper | Pull articles from publisher feeds |

| Processing Layer | Kafka, Article Processing Pipeline | Deduplicate, categorize, enrich articles |

| Storage Layer | PostgreSQL, Elasticsearch, Redis, S3 | Persist and index articles for different access patterns |

| Serving Layer | CDN, API Gateway, Feed/Search/Trending Services | Handle client requests with low latency |

Let us walk through each layer in detail.

Ingestion Layer

The problem we're solving: We need to continuously discover and fetch new articles from ~50,000 publishers, each of which publishes content at different rates, in different formats, with different reliability characteristics.

The Scheduler

The Scheduler is the orchestrator of the ingestion layer. It maintains a registry of all publishers (stored in PostgreSQL) and is responsible for deciding when to fetch each publisher's feed.

How it works:

- The Scheduler runs as a periodic process (every 30 seconds, it checks which publishers are due for a fetch). For each publisher whose next fetch time has passed, it enqueues a fetch task. The simplest implementation is a database-backed job queue: the Scheduler queries for publishers where next_fetch_at <= NOW(), enqueues them, and updates next_fetch_at to NOW() + fetch_interval.

- Leader election: If we run multiple Scheduler instances for redundancy (and we should, for availability), we need to ensure only one is actively scheduling at any time, to avoid duplicate fetches. We use ZooKeeper for leader election. All Scheduler instances attempt to acquire a ZooKeeper lock; only the leader actually schedules. If the leader dies, another instance acquires the lock within seconds. This is a standard pattern and ZooKeeper is battle-tested for this purpose.

- Why not a simple cron job? A cron job on a single machine is a single point of failure. If that machine goes down, ingestion stops. ZooKeeper-based leader election with multiple candidate instances gives us high availability for the scheduling function.

Publisher polling intervals vary: Not all publishers need to be fetched at the same frequency. We assign publishers to priority tiers:

- Tier 1 (major outlets — NYT, BBC, Reuters, CNN): Every 1-2 minutes. These publishers produce the most important news and publish frequently. Users expect their content to appear almost immediately.

- Tier 2 (mid-size/regional): Every 5 minutes. Important but less time-sensitive.

- Tier 3 (small/niche): Every 10-15 minutes. Infrequent publishers where a slight delay is acceptable.

The Scheduler can dynamically adjust tiers based on observed publishing frequency. If a Tier 3 publisher suddenly starts publishing multiple articles per hour (e.g., during a local crisis), it can be temporarily promoted to Tier 2 or Tier 1.

Feed Fetcher Workers

Feed Fetcher Workers are the workhorses that actually make HTTP requests to publisher endpoints. They are stateless, horizontally scalable workers that consume fetch tasks from the Scheduler's queue.

How they work:

- A worker picks up a task: "Fetch publisher 'reuters', feed URL: https://feeds.reuters.com/reuters/topNews".

- It makes an HTTP GET request to the feed URL with appropriate headers (If-Modified-Since, If-None-Match for conditional fetching — more on this in the deep dives).

- It parses the RSS/Atom XML response and extracts individual article entries.

- For each article, it constructs a raw article message containing:publisher_id, title, description, source_url, published_at, image_url.

Note: it might save the raw response in S3 for running ML model or analysing the content

- It publishes these messages to the raw-articles Kafka topic.

Why horizontally scalable? With 50,000 publishers and fetch intervals ranging from 1-15 minutes, we might have ~10,000-20,000 fetches to perform per minute at peak. A single worker making sequential HTTP requests (each taking 200ms-2s depending on the publisher's response time) would be too slow. With 20-50 workers operating in parallel, each handling different publishers, we easily keep up.

ZooKeeper for work distribution: We use ZooKeeper to assign publisher partitions to workers. Each worker is assigned a range of publisher IDs and is responsible for fetching only those publishers. If a worker dies, ZooKeeper detects the failure and re-assigns its publishers to surviving workers. This avoids the scenario where two workers fetch the same publisher simultaneously (which would waste resources and potentially trigger rate limits on the publisher's side).

Handling publisher failures gracefully: Publishers go down. Their RSS feeds return 500 errors, timeout, or serve malformed XML. Our workers must handle all of these cases:

- On transient failure (5xx, timeout): Retry with exponential backoff (1s, 2s, 4s...). After 3 retries, skip this fetch cycle and try again at the next scheduled interval.

- On persistent failure (multiple cycles): Mark the publisher as "unhealthy" in the registry. Reduce fetch frequency. Alert the operations team.

- On malformed response: Log the error, skip the response, continue with the next publisher. Never let a single publisher's bad data crash the worker.

Rate limiting: Some publishers will rate-limit our requests. We respect their robots.txt and rate limit headers. Each worker maintains a per-publisher rate limiter and backs off when it receives 429 (Too Many Requests) responses.

Processing Pipeline

The problem we're solving: Raw articles from publishers are messy. They may be duplicates, they lack standardized categorization, their images are in varying formats and sizes, and their summaries may be absent or inconsistent. We need a pipeline that transforms raw articles into clean, enriched, deduplicated articles ready for storage and serving.

Kafka as the Backbone

We place Apache Kafka at the center of the processing pipeline. Kafka is a distributed streaming platform that acts as a durable, ordered buffer between producers (Feed Fetcher Workers) and consumers (Article Processing Workers).

Why Kafka and not a simpler message queue like RabbitMQ or SQS?

- Durability and replay: Kafka persists messages to disk. If the processing pipeline goes down for an hour (e.g., during a deployment), no articles are lost — they sit in Kafka waiting to be consumed when the pipeline comes back up. With a traditional queue, messages are typically deleted upon consumption; replaying is difficult.

- Multiple consumers: A single Kafka topic can have multiple independent consumer groups. Our processed-articles topic is consumed by four different systems (PostgreSQL worker, Elasticsearch indexer worker, Redis feed updater, thumbnail uploader). With Kafka, each consumer group tracks its own offset and processes messages at its own pace. With a traditional queue, we'd need to publish to four separate queues.

- Ordering: Kafka guarantees ordering within a partition. We partition the raw-articles topic by publisher_id, which means all articles from the same publisher are processed in order. This matters for deduplication — we want to process articles from the same publisher sequentially to detect duplicates reliably.

- Scalability: Kafka handles millions of messages per second. Our 29 articles/second ingestion rate is trivial for Kafka, but the headroom is reassuring and means we never need to worry about the ingestion path becoming a bottleneck.

We use two Kafka topics:

- raw-articles: Fed by Feed Fetcher Workers. Contains unprocessed article data as extracted from RSS feeds.

- processed-articles: Fed by Article Processing Workers. Contains enriched, deduplicated, categorized articles ready for storage.

Article Processing Workers

These workers consume from the raw-articles topic and perform a series (these are sequential) of transformations:

Step 1: Deduplication

This is perhaps the most important processing step. The same breaking news story — say, a major earthquake — will be reported by hundreds of publishers simultaneously. Without deduplication, our feed would be filled with dozens of nearly identical articles about the same event.

We use a two-level deduplication strategy:

- Exact dedup (URL-based): The simplest check. If we've already ingested an article with the exact same source_url, it's a duplicate. We maintain a Redis set of all ingested URLs from the last 72 hours. This catches the most obvious duplicates — the same article being referenced in an RSS feed that we fetch multiple times.

- Near-duplicate dedup (content-based): More interesting. Different publishers will write different articles about the same event, with different URLs but very similar content. We use SimHash — a locality-sensitive hashing algorithm — to compute a fingerprint of the article's title + first 200 words. Articles with SimHash similarity > 80% are considered "near-duplicates." Rather than dropping them entirely, we group them into "story clusters" — one article becomes the "lead" (typically from the highest-priority publisher), and the others are linked as "More coverage." This is exactly what Google News does.

The implementation details of SimHash are worth understanding: it produces a 64-bit hash where similar documents produce hashes that differ in only a few bits. By checking the Hamming distance between a new article's SimHash and recent SimHashes (stored in Redis), we can efficiently find near-duplicates. A Bloom filter over SimHashes gives us O(1) approximate membership testing.

Step 2: NLP Categorization

Each article needs to be assigned to one or more categories (World, Business, Technology, Sports, Entertainment, Science, Health). There are several approaches:

- RSS category tags: Many RSS feeds include category tags. When present, these are the most reliable signal and we use them directly.

- ML-based classification: When RSS tags are absent or unreliable, we run the article's title and summary through a lightweight text classification model. This can be a simple TF-IDF + logistic regression model, or a fine-tuned BERT-small model. The model is pre-trained on a labeled dataset of articles and their categories. It runs in < 50ms per article, which is fast enough for our 29 articles/second ingestion rate.

- Rule-based fallback: For edge cases where the ML model has low confidence, we fall back to keyword-based rules (e.g., if the title contains "NBA," "FIFA," or "Olympics," categorize as Sports).

We assign a primary category and optionally a secondary category. An article about "Tech Companies' Role in Climate Policy" might be categorized as both Technology and Science.

Step 3: Thumbnail Extraction and Processing

Users expect to see images in their news feed. For each article, we need a thumbnail image. The extraction process:

- Check if the RSS feed provides a <media:content> or <enclosure> element with an image URL. If so, use it.

- Failing that, check the article's source page for an Open Graph og:image meta tag. This requires a quick HTTP request to the article URL and parsing the HTML <head>. We use a lightweight HTTP client with a 2-second timeout.

- Failing that, extract the first <img> tag from the article body (if the RSS feed includes full content).

- As a final fallback, use a default placeholder image for the publisher.

Once we have an image URL, we:

- Download it.

- Resize it to standard thumbnail dimensions (e.g., 400x225 for a 16:9 aspect ratio).

- Convert it to WebP format for efficient delivery.

- Upload it to S3 with a predictable key pattern: thumbnails/{article_id}.webp.

- Construct the CDN URL: https://cdn.newsagg.com/thumbs/{article_id}.webp.

Step 4: Content Enrichment

If the RSS feed's description field is empty or too short, we generate a summary:

- Extract the first 200 characters of the article body (if available in the RSS content).

- Clean HTML tags, normalize whitespace.

- Store as the article's summary field.

After all four steps, the enriched article is published to the processed-articles Kafka topic.

Storage Layer

The problem we're solving: Processed articles need to be persisted in a way that supports four very different access patterns: (1) feed retrieval by category and time, (2) full-text search by keywords, (3) thumbnail image serving, and (4) trending article computation. No single storage technology optimally serves all four patterns. We use a polyglot persistence approach — multiple specialized stores, each optimized for its access pattern.

This is a key level insight. Junior candidates often try to serve everything from a single database. Senior candidates recognize that the performance, scaling, and operational characteristics of different data stores make them suitable for different purposes, and they are comfortable with the added complexity of maintaining multiple stores in exchange for superior performance.

PostgreSQL — Source of Truth

PostgreSQL stores the canonical, durable copy of all article and publisher data. It is the source of truth — if Redis and Elasticsearch were wiped clean, we could rebuild them entirely from PostgreSQL.

Schema1CREATE TABLE publishers (

2 id UUID PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT gen_random_uuid(),

3 name TEXT NOT NULL,

4 base_url TEXT NOT NULL,

5 feed_url TEXT NOT NULL,

6 feed_format TEXT DEFAULT 'rss', -- 'rss', 'atom', 'api'

7 fetch_interval INT NOT NULL DEFAULT 600, -- seconds

8 priority_tier INT NOT NULL DEFAULT 3, -- 1=high, 2=mid, 3=low

9 is_active BOOLEAN DEFAULT true,

10 last_fetched_at TIMESTAMP,

11 next_fetch_at TIMESTAMP,

12 created_at TIMESTAMP DEFAULT NOW()

13);

14

15CREATE TABLE articles (

16 id UUID PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT gen_random_uuid(),

17 publisher_id UUID NOT NULL REFERENCES publishers(id),

18 title TEXT NOT NULL,

19 summary TEXT,

20 source_url TEXT NOT NULL UNIQUE,

21 thumbnail_url TEXT,

22 category TEXT NOT NULL, -- 'world', 'business', 'tech', etc.

23 published_at TIMESTAMP NOT NULL,

24 content_hash BIGINT, -- SimHash for deduplication

25 cluster_id UUID, -- story cluster for near-duplicates

26 created_at TIMESTAMP DEFAULT NOW()

27) PARTITION BY RANGE (published_at);

28

29-- Partition by month for efficient time-range queries and data lifecycle management

30CREATE TABLE articles_2026_01 PARTITION OF articles

31 FOR VALUES FROM ('2026-01-01') TO ('2026-02-01');

32CREATE TABLE articles_2026_02 PARTITION OF articles

33 FOR VALUES FROM ('2026-02-01') TO ('2026-03-01');

34-- ... more partitions

35

36-- Indexes

37CREATE INDEX idx_articles_category_published ON articles (category, published_at DESC);

38CREATE INDEX idx_articles_content_hash ON articles (content_hash);

39CREATE INDEX idx_articles_cluster ON articles (cluster_id);

40CREATE INDEX idx_publishers_next_fetch ON publishers (next_fetch_at) WHERE is_active = true

41Why table partitioning? Partitioning the articles table by published_at (monthly partitions) gives us two benefits:

- Query performance: Feed queries always filter by recency (we only show articles from the last 72 hours). With partitioning, PostgreSQL only scans the current month's partition, not the entire table of millions of historical articles.

- Data lifecycle: Old partitions can be archived (moved to cold storage) or dropped entirely. A 3-month retention policy is as simple as dropping partitions older than 3 months.

Why PostgreSQL specifically? PostgreSQL is a reliable, feature-rich relational database with excellent support for indexing, partitioning, and full ACID transactions. For our article data model (structured, relational — articles belong to publishers), a relational database is the natural fit. We don't need the extreme write throughput of Cassandra/DynamoDB (remember, we only write 29 articles/second), so we can enjoy PostgreSQL's strong consistency guarantees, rich querying capabilities, and mature ecosystem.

Read replicas: We deploy PostgreSQL with 3-5 read replicas behind a connection pooler (PgBouncer). The primary handles all writes (ingestion). Reads from the Feed Service (on cache miss) are distributed across replicas. Replication lag of a few seconds is acceptable given our AP consistency model.

The full article body was never carried forward. The raw S3 object had it, but that's treated as temporary staging. So in this architecture as described, PostgreSQL likely only stores that same set of enriched metadata fields — not the full article body.

This is actually intentional for a news aggregator. Unlike a read-it-later app (Pocket, Instapaper), a news aggregator like Google News doesn't store the full article content at all. When a user clicks an article, you redirect them to the publisher's original URL — source_url. You're not serving the content yourself.

Elasticsearch — Full-Text Search

Elasticsearch is a distributed search engine built on Apache Lucene. It is purpose-built for full-text search with features like stemming, tokenization, relevance scoring, and faceted filtering.

Why a separate search index? PostgreSQL has full-text search capabilities (tsvector/tsquery), but they are limited compared to Elasticsearch:

- PostgreSQL's FTS lacks sophisticated relevance ranking (e.g., boosting recent articles, factoring in publisher authority).

- PostgreSQL's FTS doesn't scale horizontally — it's bounded by the single-node performance of the database.

- Elasticsearch's inverted index is optimized for the "find all documents containing these keywords" access pattern, whereas PostgreSQL's B-tree indexes are optimized for exact-match and range queries.

For a system serving 100M users with search as a core feature, a dedicated search engine is the right choice.

Index mapping:

1{

2 "mappings": {

3 "properties": {

4 "title": { "type": "text", "analyzer": "english" },

5 "summary": { "type": "text", "analyzer": "english" },

6 "category": { "type": "keyword" },

7 "publisher_name": { "type": "keyword" },

8 "published_at": { "type": "date" },

9 "source_url": { "type": "keyword", "index": false }

10 }

11 }

12}

13We use the english analyzer for title and summary, which applies stemming (so "running" matches "run"), stop-word removal, and lowercasing. category and publisher_name are keyword fields (exact match) for filtering.

Deployment: A 3-node Elasticsearch cluster with 1 replica per shard. For ~2.5M documents/day with a 30-day retention, we're storing ~75M documents — well within a 3-node cluster's capacity. Indices are created per week and aliased for querying.

Redis — Feed Cache and Trending

Redis is an in-memory data structure store that we use for two critical purposes:

1. Pre-computed Feed Sorted Sets

This is the most important use of Redis in our architecture and the key to achieving < 200ms feed latency. For each category, we maintain a Redis Sorted Set where:

- Each member is an article ID.

- Each score is the article's

published_attimestamp (as a Unix epoch number).

1Key: feed:world

2Type: Sorted Set

3Members: { (article_id_1, 1707570600), (article_id_2, 1707570500), ... }"1Key: feed:technology

2Type: Sorted Set

3Members: { (article_id_3, 1707570400), (article_id_4, 1707570300), ...}"When a new article is processed, the Feed Materializer (a consumer of the processed-articles Kafka topic) adds it to the appropriate sorted set(s):

1ZADD feed:world 1707570600 "article_id_1"When a user requests GET /v1/feed?category=world&limit=20, the Feed Service executes:

1ZREVRANGEBYSCORE feed:world +inf -inf LIMIT 0 20This returns the 20 most recent article IDs in the "world" category in O(log N + 20) time — typically under 1 millisecond. We then batch-fetch the article details from a Redis hash map:

1HMGET article:uuid-123 title summary thumbnail_url publisher_name published_at source_urlThe total Redis operation takes 2-5ms, compared to 50-200ms for an equivalent PostgreSQL query.

2. Article Detail Cache

Each article's display data is cached as a Redis Hash:

1Key: article:uuid-123

2Type: Hash

3Fields: { title: "...", summary: "...", thumbnail_url: "...", publisher_name: "...", ... }"This avoids hitting PostgreSQL for individual article lookups, which happen millions of times per day as we resolve article IDs from sorted set queries into full FeedItem responses.

3. Trending Articles

We maintain a Redis Sorted Set for trending articles, where the score is a computed "trending score" based on:

- Number of clicks in the last 2 hours (from click event stream)

- Number of publishers covering the same story cluster

- Recency

1Key: trending:global

2Type: Sorted Set

3Members: { (article_id_5, 9500), (article_id_6, 8200), ... }A background worker recomputes trending scores every 5 minutes.

4. Deduplication Data

As discussed, Redis stores:

- A Set of recently ingested source URLs (for exact dedup).

- SimHash values for near-duplicate detection.

- A Bloom filter for fast approximate membership testing.

Redis cluster: We deploy Redis as a 3-node cluster with 1 replica per node for high availability. Data is sharded by key prefix (e.g., all feed:* keys on one shard, all article:* keys on another) to distribute load evenly.

S3 — Blob Storage for Media

Amazon S3 (or equivalent) stores thumbnail images, publisher logos, and any other binary assets. S3 is chosen because:

- It's effectively infinitely scalable for storage.

- It's extremely durable (11 nines).

- It integrates seamlessly with CDNs (CloudFront can serve directly from S3 origins).

- It's cost-effective for large volumes of infrequently-modified binary data.

Thumbnails are stored with predictable key paths (thumbnails/{article_id}.webp) and served through the CDN with long cache TTLs (images don't change once uploaded).

Serving Layer

The problem we're solving: We need to handle ~17,000 requests/second at peak with < 200ms P99 latency while remaining highly available during failures and traffic spikes.

CDN (Content Delivery Network)

The CDN is the first line of defense against load. It sits between users and our servers, caching responses at edge locations around the world.

What we cache at the CDN:

- Thumbnail images: Long TTL (24 hours). Images don't change once uploaded.

- Publisher logos: Long TTL (7 days). Rarely change.

- Anonymous feed responses: Short TTL (2-5 minutes). For users who are not logged in (the majority of news consumers), the feed is the same for everyone viewing a given category. We can cache the response for GET /v1/feed?category=world&limit=20 at the CDN and serve it to millions of users from edge servers, never hitting our backend at all.

Impact: The CDN absorbs roughly 40-60% of all requests. For a breaking news event where millions of users simultaneously load the same "Top Stories" feed, the CDN is the difference between our backend handling 17K QPS and handling 7K QPS. That reduction alone might save us from needing to scale up servers.

API Gateway / Load Balancer

All requests that miss the CDN arrive at the API Gateway, which provides:

- Request routing: Directs /v1/feed/* requests to the Feed Service, /v1/search/* to the Search Service, /v1/trending to the Trending Service.

- Rate limiting: Per-client rate limits to prevent abuse and protect backend services.

- Authentication: Validates auth tokens and extracts user identity.

- Load balancing: Distributes requests across multiple instances of each backend service using round-robin or least-connections.

We use a standard setup: an application-level API gateway (e.g., Kong, or a custom Gateway built on Nginx/Envoy) backed by a layer 4 load balancer (AWS ALB/NLB) for horizontal scaling.

Feed Service

Cache-aside (what most systems actually do)

The Feed Service is the core backend service. It handles the GET /v1/feed and GET /v1/articles/{id} endpoints.

Request flow for GET /v1/feed?category=tech&cursor=abc&limit=20:

- Parse the cursor token. Decode the base64 cursor to extract (last_published_at, last_article_id).

- Query Redis: ZREVRANGEBYSCORE feed:tech last_published_at -inf LIMIT 0 21 (we fetch 21 to know if there's a "next page").

- Batch-fetch article details from Redis: HMGET article:{id} ... for each of the 20 article IDs.

- If any article details are missing from Redis (cache miss), fall back to PostgreSQL read replica.

- Construct the response, including the next_cursor from the 20th item's (published_at, article_id).

- Return the response.

Horizontal scaling: The Feed Service is stateless — it reads from Redis and PostgreSQL but maintains no local state. We run 10-20 instances behind the load balancer and auto-scale based on CPU utilization and request count (Kubernetes HPA).

Search Service

The Search Service handles the GET /v1/search endpoint. It translates the user's query into an Elasticsearch query:

1{

2 "query": {

3 "bool": {

4 "must": [

5 { "multi_match": { "query": "climate summit", "fields": ["title^2", "summary"] } }

6 ],

7 "filter": [

8 { "term": { "category": "world" } },

9 { "range": { "published_at": { "gte": "now-30d" } } }

10 ]

11 }

12 },

13 "sort": [

14 { "_score": "desc" },

15 { "published_at": "desc" }

16 ],

17 "size": 20

18}

19Note the title^2 boost — matches in the title are weighted twice as heavily as matches in the summary. We also filter to the last 30 days and the specified category. Results are sorted by a blend of relevance score and recency.

Caching search results: Popular search queries (e.g., "election," "stock market") are cached in Redis with a 30-60 second TTL. This avoids hitting Elasticsearch repeatedly for the same query.

Trending Service

The Trending Service handles GET /v1/trending. It simply reads the top N entries from the trending:global Redis sorted set. This is an O(log N) operation that completes in < 1ms. Stateless and trivially scalable.