Zookeeper is a robust service that aims to deliver coordination among distributed systems so that the application developers don't have to spend their entire time fretting about the coordination logic but focus on what they are best at, i.e., their application logic.

Using ZooKeeper, the application developers can implement common coordination tasks, such as leader election, managing group membership, i.e., who has what job on their plate, and managing metadata.

You might be curious as to why it is named ZooKeeper. The team behind this was notorious for using animal names, such as Apache Pig, Apache Camel, Apache Tomcat, etc. Since these applications are named after animals and must be managed, it made sense to call the service that manages them ZooKeeper. After all, distributed systems seem zoo; they are chaotic and difficult to manage, so you need someone who can manage them, and thus Zookeeper comes into play.

Background

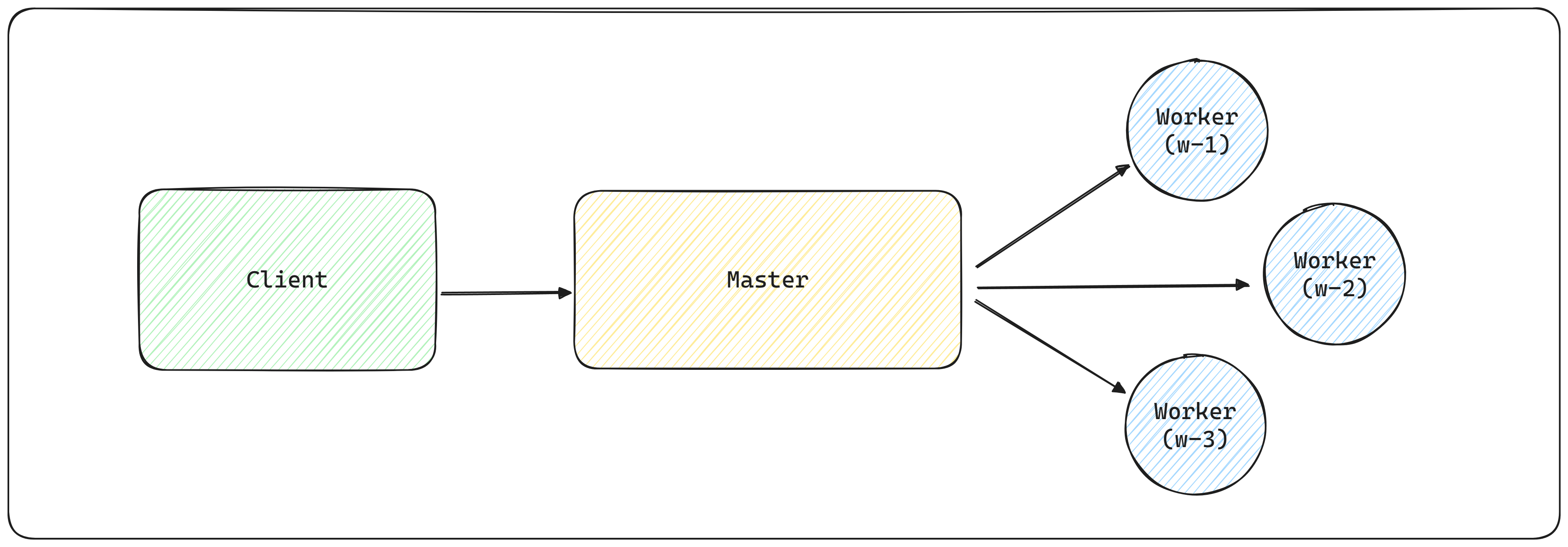

Let's understand the importance of ZooKeeper using Master Worker Architecture:

Master-Worker Architecture

It is one of the most well-known architectures that has been used extensively in the realm of distributed systems. Think of HBase, a clone of Google's Big Table, which uses Master-Worker architecture.

In a typical master-worker architecture, a master process is responsible for keeping track of the workers and tasks available and for assigning tasks to workers. To implement a master-worker system, we must solve three fundamental problems:

- Master Failures: if the master is faulty and becomes unavailable, the system cannot allocate new tasks or reallocate tasks from workers who have also failed.

- Worker Failures: If a worker crashes, the tasks assigned to it will not be completed.

- Communication failure: If the master and a worker cannot exchange messages, the Worker might not learn of new tasks assigned to it.

To deal with these issues, the system must be able to reliably elect a new master if the previous one is faulty, determine which workers are available, and decide when a worker's state is stale with respect to the rest of the system.

Let's look at each of them in more detail:

Master Failures

Consider what happens when your manager goes on leave in a corporate setting. Or when a CEO resigns without any notice? The management promotes someone within the team to act as manager or an interim CEO. In the real world, it usually is easy, but in a distributed world, this is more complex.

To have our system running smoothly, we need to have a backup master. When the primary master crashes, the backup master takes over the role of the primary master. The new master must be able to recover the state of the system at the time the old master crashed. How do we do that? Since the master has crashed, we can't rely on pulling the state from it. We need to have that state somewhere else. This is where our Zookeeper comes into the picture. That someplace is the Zookeeper.

But what if the primary master never crashed? Say, it was not responsive because of an unusual load, but the backup master thought that the primary master had crashed. This will lead to a problem called split-brain, where there are two masters not aware of each other. This will lead to inconsistent behavior because the workers will be confused about which master to serve.

Worker Failures

The client submits the task to the master; the master assigns the task to its workers.

The usual flow is clients submit tasks to the master, which assigns the tasks to available workers. The Worker receives assigned tasks and reports the execution status once these tasks have been executed. The master then informs the clients of the result of the execution.

If a worker crashes, all tasks assigned to it and not completed must be reassigned. The first requirement here is to give the master the ability to detect worker crashes. The master must be able to detect when a worker crashes and must be able to determine what other workers are available to execute its tasks.

This is done by asking the workers to send a heartbeat to the Zookeeper. If the Zookeeper doesn't receive the response, it deletes the Worker, and the master is notified about this incident so that it can take appropriate action.

Communication Failures

If a worker becomes disconnected from the master due to a network partition, reassigning a task could lead to two workers executing the same task. If running a task more than once is acceptable, we can reassign without verifying whether the first Worker has executed the task. If it is not acceptable, then the application must be able to accommodate the possibility that multiple workers may end up trying to execute the task.

Using locks for tasks (as with the case of master election) is not sufficient to avoid having tasks executed multiple times because we can have, for example, the following succession of events:

- Master M1 assigns task T1 to Worker W1.

- W1 acquires the lock for T1, executes it, and releases the lock.

- Master M1 suspects that W1 has crashed and reassigns task T1 to Worker W2.

- W2 acquires the lock for T1, executes it, and releases the lock

Here, the lock over T1 did not prevent the task from being executed twice because the two workers did not interleave their steps when executing the task.

Another critical issue with communication failures is their impact on synchronization primitives like locks. Because nodes can crash and systems are prone to network partitions, locks can be problematic: if a node crashes or gets partitioned away, the lock can prevent others from making progress.

ZooKeeper consequently needs to implement mechanisms to deal with such scenarios. First, it enables clients to say that some data in the ZooKeeper state is ephemeral. Second, the ZooKeeper ensemble requires that clients periodically notify the ZooKeeper that they are alive. If a client fails to notify the ensemble promptly, then all ephemeral states belonging to this client are deleted. Using these two mechanisms, we can prevent clients individually from bringing the application to a halt in the presence of crashes and communication failures.

ZooKeeper Basics

Zookeeper uses a filesystem-like API comprising a small set of calls that enable applications to implement their logic.

Zookeeper contains small data nodes, which they refer to as znodes, that are organized hierarchically as a tree, similar to a filesystem.

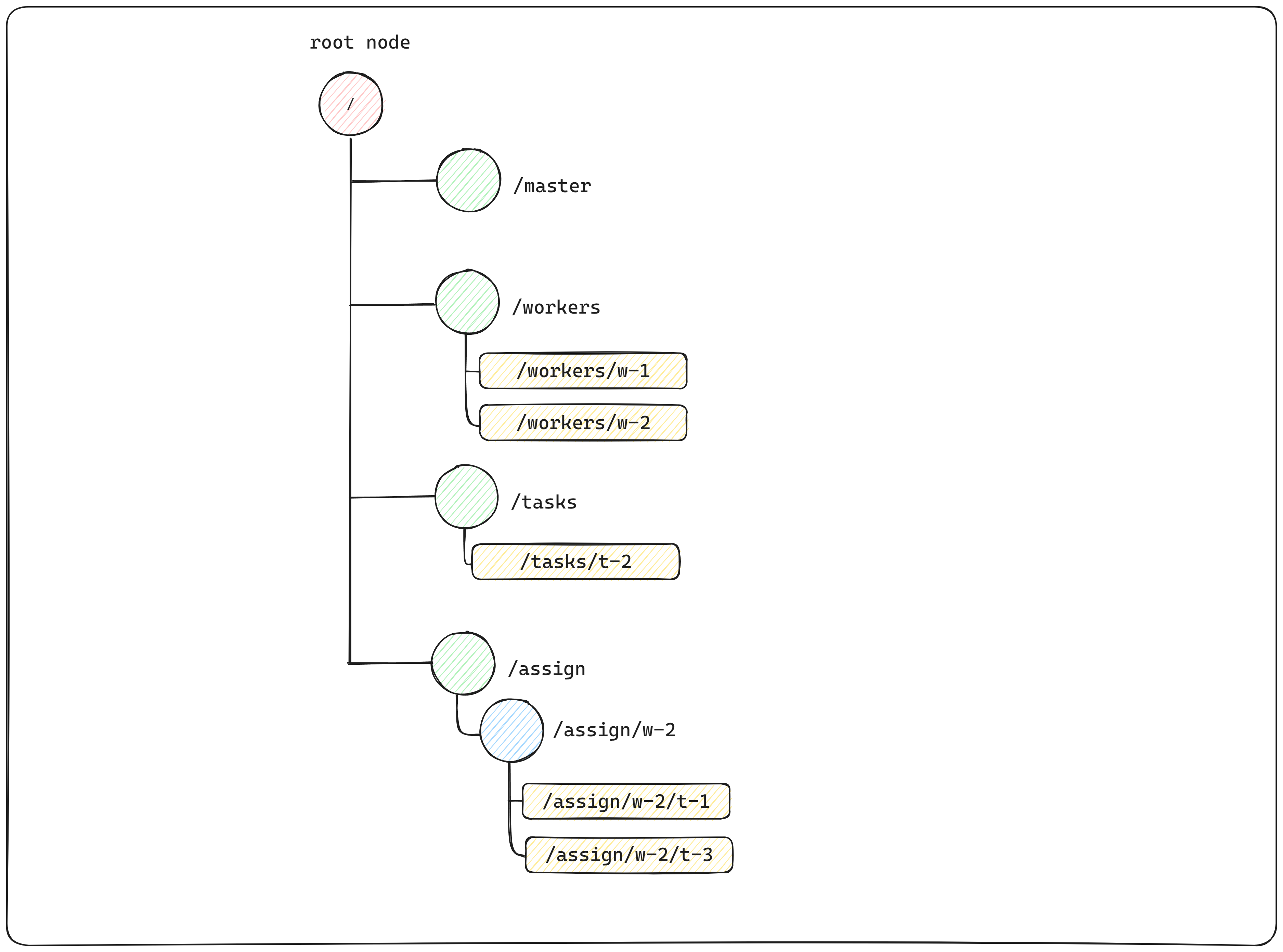

ZooKeeper data tree example

In the above figure, the root node contains four more nodes, and three of those nodes have nodes under them. The leaf nodes are the data (represented as rectangle blocks).

Notice the node that doesn't contain the data is our master znode. The absence of a master znode means that no master is currently elected.

- The /workers znode is the parent node of all the znodes representing workers available in the system. In the figure, we can see there are two workers available at /workers/w-1and at /workers/w-2

- The /tasks znode is the parent of all tasks created and that are waiting for workers to execute them. Clients of the master-worker application add new znodes as children of /tasks znode to represent new tasks.

- The /assign znode is the parent of all the znodes representing an assignment of a task to a worker. The above figure means that currently, the Worker (w-2) is executing task (t-1) and task (t-3). Notice that t-1 and t-3 are not present under /tasks because it is already being picked up and executed by worker w-2. All the tasks assigned to the Worker (w-2) will be there under /assign/w-2

But how do I create all these znode? The ZooKeeper API exposes the following operations:

- create /path data: Creates a znode named /path containing data.

- delete /path: Deletes the znode /path.

- exists /path: Checks whether /path exists.

- setData /path data: Sets the data of znode /path to data.

- getData /path: Returns the data in /path.

- getChildren /path: Returns the list of children under /path.

One important note is that ZooKeeper does not allow partial writes or reads of the znode data. When setting the data of a znode or reading it, the content of the znode is replaced or read entirely.

Note: ZooKeeper clients connect to a ZooKeeper service and establish a session through which they make API calls.Znode

While creating a znode, one needs to provide a mode. The mode determines how the znode behaves. We have:

Persistent and ephemeral znodes

A znode can be either persistent or ephemeral. A persistent znode/path can be deleted only through a call todelete API. On the other hand, an ephemeral node is deleted if the client that created it fails to notify the Zookeeper about its existence or closes its connection with it.

Persistent znodes store data for an application, lasting even if the creator leaves the system. For example, in a master-worker setup, task assignments to workers need persistence, even if the master crashes./assign and /tasks are persistent nodes.

Ephemeral znodes convey information only while the creator's session is valid. In the master-worker example, the master's znode is ephemeral, indicating an active master. If it persists after the master is gone, the system can't detect the crash, hindering progress. Workers also use ephemeral znodes, disappearing automatically if the Worker becomes unavailable. /masters and /workers are ephemeral nodes.

Sequential znodes

Sequential znodes receive a unique, increasing integer added to their path. For instance, creating a sequential znode at /tasks/t- results in a path like /tasks/t-1, where "1" is the assigned sequence number. This system ensures unique names and reveals the creation order of znodes.

In our context, examples of sequential znodes include /workers/w-1, /workers/w-2, and tasks/t-2.

Watches and Notifications

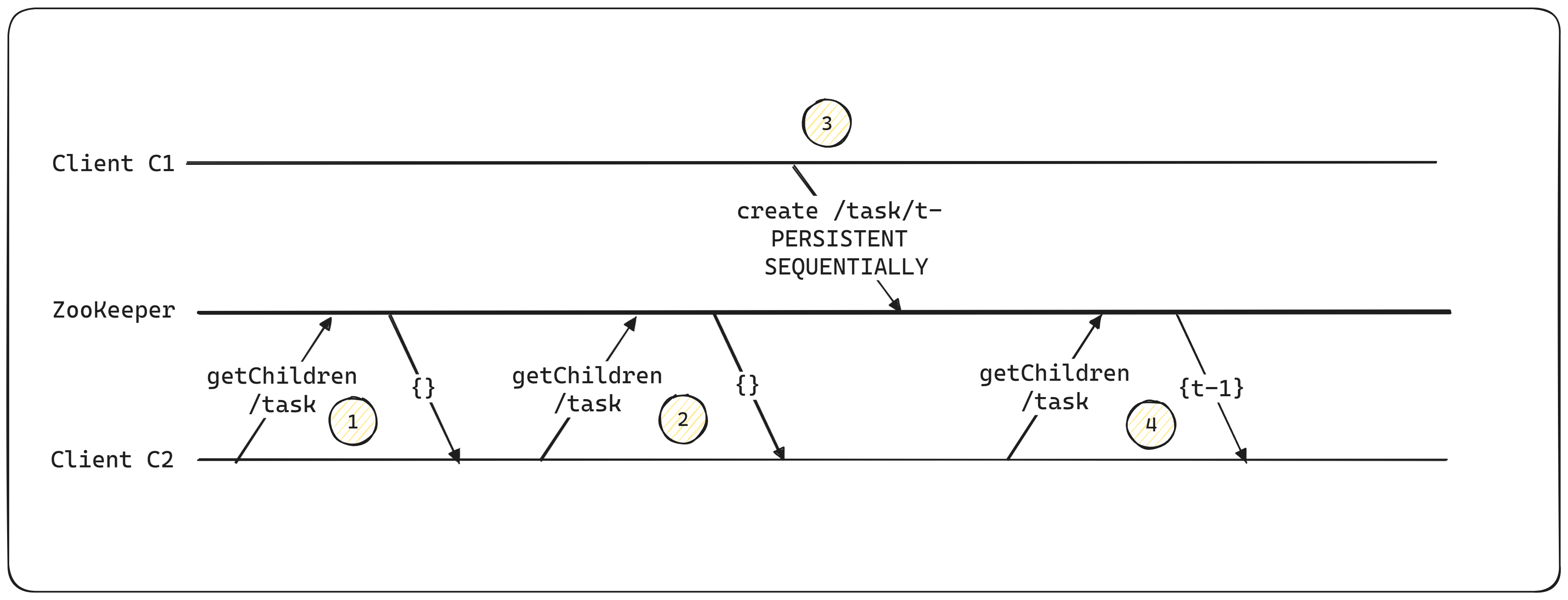

Since ZooKeeper is typically accessed as a remote service, accessing a znode every time a client needs to know its content would be very expensive: it would induce higher latency and more operations to a ZooKeeper installation. Let's take an example to understand the pain points.

Multiple reads to the same znode

In the above figure,

- Client C2 reads the list of tasks; initially empty, it returns {} (an empty list).

- Client C2 checks again for new tasks by reading the znode.

- Client C1 creates a new task using create /task/t- PERSISTENT SEQUENTIAL, resulting in the task /tasks/t-1.

- Client C2 reads the znode again, finding the updated list: {t - 1}.

Here, the client, C2, is polling for new tasks, and most of the time, it is not necessary. Unless client C1 creates a new task, no matter how many times client C2 asks for the task, the Zookeeper will always return an empty task list.

ZooKeeper employs a notification-based mechanism to replace client polling. Clients register for notifications on znode changes by setting a watch. A watch is a one-shot operation, meaning it triggers a single notification. For continuous notifications, clients need to set a new watch after each received notification.

This is how the whole process changes after a client registers for the watch.

Using notifications to be informed of changes to a znode

- Client C2 reads the initially empty list of tasks and sets a watch for changes using set watch.

- Client C1 creates a new task in ZooKeeper, triggering a notification to client C2.

- Client C2, notified of the change, reads the children of /tasks and observes the new task.

Conclusion

We have gone through a number of basic ZooKeeper concepts in this article. We understood the znodes and their importance. We also delved into watchers and notifications. In the follow-up article, I'll be delving into how one can implement a leader election via Zookeeper.Stay tuned. Thanks.